Research

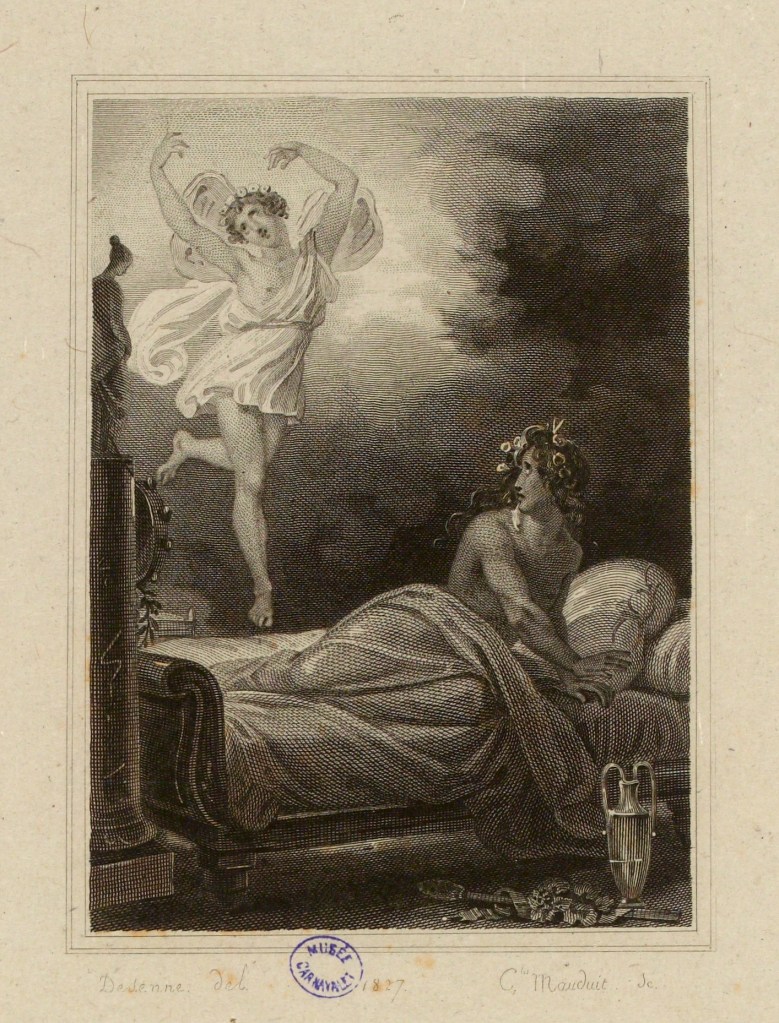

Frontispice for Berchoux’s La danse ou La guerre des Dieux de l’Opéra, drawn by Alexander-Joseph Desenne [1827], and engraved by Charles-Louis Victor Mauduit, 1829. Paris, Musée Carnavalet, G.12381. CC0 1.0.

My doctoral research at the Université Côte d’Azur focuses on the embodiment of archaeological trends and aesthetics in dance practices, from the last decade of the 18th century until the late 1820s. I explore the awareness of the classical past as a sensitive experience of individuals, from how the dance imaginary is influenced by new visual and spatial elements issued from excavations, to how body techniques express society’s taste for antiquities. The study of ancient iconography and a modern sense of physical expansion characterize the corporeality of this age. The latter is elaborated by a multitude of artists that circulate between the European opera houses, as well as in royal palaces, museums, salons, and private collections. A crossed-archival research in several cities allows me to retrace the networks of dancers, musicians, and ballet masters that were part of a wide artistic community, a real “ballet industry” focused on antiquities and projected into modernity.

Dessinez-vous avec goût et naturellement dans la moindre des poses ; il faut que le danseur puisse, à chaque instant, servir de modèle au peintre, au sculpteur.

Carlo Blasis

In the second half of the 18th century, the disclosure of south-Italian archaeological discoveries, together with political and social changes, made an impact on trends and people’s minds. These phenomena influenced the development of a new visual culture. My dissertation investigates how, between the 18th and 19th centuries, dance practices incorporated the aesthetic values of classical art, and how the expansion of ballet technique enabled the dancers to express social fascination for antiquities. A meticulous collection of archival sources supports this research and allows me to retrace the dense network of transcultural and intercultural relationships among European centers.

Through a transdisciplinary approach, I analyze the dance network across Austria, England, France, and Italy, the diffusion of dance books and engravings among dancers, as well as their own documents (such as experimental notation systems, annotated music scores, and stage drawings).

The research done so far is based on several questions. Which physical parameters—body placements, timing, muscle tones, space levels—were stimulated in order to convey a sense of antiquity? Does the experience of museums and collections shape a dancer’s vision? How do ballet masters follow, unfollow, or even anticipate the neoclassical trends? Which difficulties arise when they re-stage a ballet of this style in different cities? When the antiques-mania phenomenon declines, what traces will it leave in body techniques?

Behind these questions we can observe a complex group of individuals, men and women extremely active in promoting their careers. Human, artistic, political, social, and economic connections were constructed thanks to an extensive network of professionals in the theatrical world (musicians, choreographers, impresarios, scenographers, etc.) who were in continual movement and were involved in performance productions. They were part of a real “ballet industry.” The conventional historiography of dance, often commissioned by the operators of their own theaters and intended to bestow a historical identity to their institutional past, has led scholars, starting in the 19th century, to organize sources and to build historical discourse from that point of observation, without adopting a multifocal perspective that constituted precisely the lifeblood of past dance practices, which instead were constructed according to a “multidirectional” logic.

Regarding the stricter methodological approach, I structured my dissertation “La corporéité archéologique: danser d’après l’antique (1786-1826)” in four main parts:

I) Considering the perception of antiquities under a phenomenological and psychological approach;

II) Analyzing the networks and those cultural tools that made the circulation possible;

III) Documenting the nature of dance practices influenced by ancient art: accessories, costumes, scenography, and length of performances, use of space and directions, musical forms (especially the adagio), body placements;

IV) Considering the epistemological and historiographical issues of common dance categories (classical, neoclassical and pre-romantic).

My research can further our understanding of Western classical dance and its relation to ancient references, while proposing the term corporéité archéologique (“archeological corporeality”) as a new definition that can describe specific body techniques based on connoisseurship research done by dance artists of the early 19th century.